The Kodak Retina IIIc - Review of the Finest German Kodak

My Retina was purchased from Central Camera of Chicago. I highly recommend them for used and new cameras, as well as servicing that hand-me-down camera you’ve received from relatives.

The History

These days, you would be hard pressed to find someone who is unfamiliar with Kodak. While the brand certainly doesn’t command the power that it once had, much of the remaining worth of the company comes down to brand recognition. Kodak remains one of the most well known names the world over. Yet while so many quickly recognize the Kodak name, far fewer people recognize the name Hasselblad, Leica, or the like. It isn’t difficult to see why, when you look at marketing techniques.

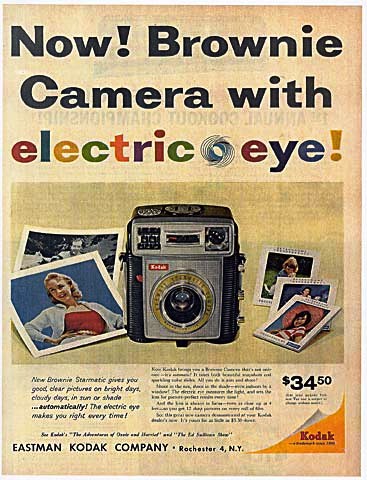

The Brownie was the every-man’s camera. It was cheap, took great photos, and if it broke, you could easily replace it.

You see, from the very beginning, George Eastman founded Kodak as the “every-man” company. You didn’t have to be wealthy to own a Kodak camera, at least compared to the company’s rivals. Kodak Brownies and the like are still so plentiful (even 100 years later) because of this very fact. Everyone had one. Everyone could afford one. This isn’t to say they were complete crap (although many were), but Mr. Eastman and the leaders that followed him certainly favored quantity over quality, and this all comes down to one simple reason: film. Kodak followed the model currently employed by printer companies everywhere: sell cheap printers that require expensive ink. In this case, film might not have been nearly as expensive as it is today, but it was certainly a consistent revenue stream. The more cameras they got into the hands of the Uncle Joes and Aunt Elizabeths of the world, the more film they sold.

Unfortunately, this recognition as a low-price, low-quality company with a printer/ink sales structure eventually led to the near failure of the company as apparently this business model doesn’t translate well to digital cameras…but that’s another story for another day. Back to the point, this is why collectors often have hoards of Kodak cameras and value them so little: they’re everywhere, and they’re practically worthless. It just so happens they make great display pieces because so many of them are so old.

Yet this value of quantity over quality, while fairly consistent, wasn’t entirely exclusive. But before we touch on the Kodak side, we need to jump back to introduce another man, this one German: Dr. August Nagel. Now every photographer knows that Germany produces some of the world’s finest cameras. I mentioned Leica above, but add to them Zeiss, Schneider, Voigtlander and multiple others who still remain dominant in today’s world of photography. For the Germans, photography remains an art. Attention to detail, fine craftsmanship, and the best of the best materials all combine to make cameras and lenses that certainly last through the ages. Interestingly enough, this seems to have always been the case. Read any founding story of Nikon or Canon and you’ll realize that both got their start by essentially ripping off Leica designs in order to make cheaper alternatives. The best has always been German.

There were a few sub-versions of the IIIc, all with small additions or feature changes. The most sought after is the IIIC (large C) which has a larger viewfinder. It often retails for $100 more than the ordinary IIIc. Otherwise, little else was changed.

So back to Dr. Nagel. While his portfolio may not be as wide ranging as Dr. Edwin Land, or other famous photography inventors, Dr. August Nagel was himself a large contributor to the art. This began with the founding of Contessa Cameras, and co-founding Zeiss Ikon (yes, the Zeiss that makes fantastic lenses and still lives on today), but continued when he split from Zeiss to start his own camera factory in his hometown of Stuttgart, Germany in 1928. While he certainly never met the notoriety of Zeiss or Leica, he did become mildly famous for his small format Nagel-Pupille camera, and apparently attracted enough attention that his small company became known in the United States.

It was around this time that Kodak was looking to spice up their game. Facing increased competition from Leica and other high-end camera manufacturers as the photography game began to expand, Kodak looked to jump into the higher end segment. Rather than develop an entirely new camera, Kodak recognized the benefit of purchasing an already-developed company within the industry, and the relatively new Nagel Camerawerks seemed to be the perfect choice. Years of experience? Check. German engineering, quality, and recognition? Check. Young enough to be at a reasonable price point (they didn’t have Leica’s name recognition)? Check.

With the purchase of Nagel Camerawerks, the company became the new German branch of Kodak, called Kodak AG Dr. Nagel Werk (Kodak already had a small presence in Germany, but not at this level). At the time, Kodak simply adopted the already-developed lineup from their new German subsidiary, but new cameras were certainly to come…and my were they beautiful. These early German Kodaks were masterpieces of metal and glass, crafted to exquisite and exacting standards that still stand up to this day. While they may not be quite as collectible as Leicas from the era, many (including myself) consider them to be almost there regarding quality and beauty. There are still few cameras that can compare to a Leica, but the Retina comes just about as close as any of them.

The Kodak Retina IIIC was the last of the folding Retinas, and the best of them all. From there, it only went down hill.

Yet while Dr. Nagel was now under the leadership of the American Kodak, he nevertheless continued to innovate. At the time, 35mm film was a fairly ubiquitous standard. While Kodak had originally debuted the 35mm standard for cinema, Leica popularized it for still imagery and by the mid 1930’s, a host of manufacturers produced cameras that utilized the format. There was only one problem: the film had to be loaded in the dark. Without a pre-loaded film cartridge, the camera itself had to be re-loaded in the dark each time. Run out of film outside during the day? Tough luck. Better find a dark room! As one can imagine, this was a problem that many sought to remedy, as it would allow greater flexibility and ease of use for the format.

Leica was the first to propose a solution, releasing a reusable canister that photographers could pre-fill in their darkrooms and insert into the camera in the field. While this certainly made the problem much less…uh…problematic, Dr. Nagel (see, I’m circling back to him) took it one step further. He proposed that Kodak, the world-wide leader in film and new owner of his business, sell 35mm film pre-loaded in cartridges. He went so far as to design the cartridges to retro-fit into existing Leica and Contax cameras, giving the format an already established group of cameras. Still, he designed an entirely new camera line that would launch with the cartridge giving users a Kodak-branded camera to kickstart it all off. This camera became the first of the Retinas…the finest cameras Kodak ever sold. Thankfully for all of us, Kodak ran with it. We still use these Nagel-designed film canisters today.

Through the years, these cameras developed and changed from the original Retina 1 (type 117) by adding new features, refining old ones, and growing sturdier, stronger, and more resilient. All in all, 11 Retina models were produced (with many sub-types). They sold well, compared favorably with the competition, and gave Kodak the high-end product they had needed to fill the void in their lineup. Unfortunately, the lineup wouldn’t last. Despite surviving a great deal of trials (including having Nagel Camerawerks’ factory taken over during WWII…Kodak eventually regained control after the war), the Retina line never had quite the profit margins that Kodak had desired. They were expensive, and few were sold. While this was generally how Leica and other German companies operated, it wasn’t the Kodak model. In 1960, the last folding Retina (considered the best Retina line) was produced. Gradually, Kodak pushed Nagel toward cheaper and more profitable models, often at the expense of quality and craftsmanship. Eventually, the lineup was nothing more than a shell of what it had formally been. Yet before this deescalation of quality, the tiny German company was able to produce one of its finest products and what many today consider to be the best Retina (and best camera all around) that Kodak ever produced: the Retina IIIc.

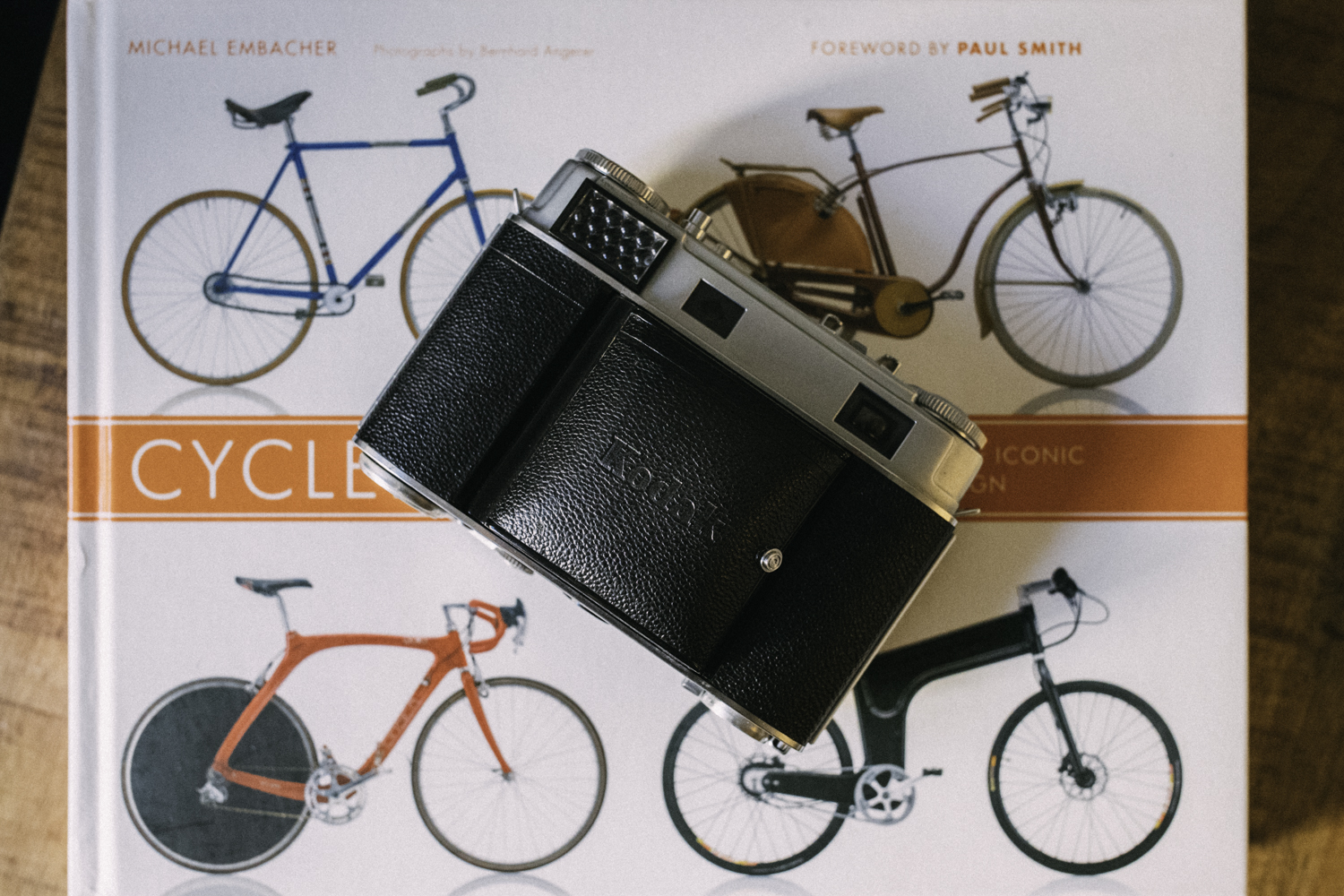

The retina is a beautiful camera. Even 64 years after it was built, this refined tank of a camera still stands up to the daily grind.

The Camera

Debuting in 1954, the IIIc was a remarkable camera for its time, and remains remarkable today. Utilizing a relatively unique folding design, the IIIc followed its predecessors by folding smaller than any SLR, yet maintaining image quality on par with its larger brethren. It was a rangefinder design, as the Retinas had been since the Retina II, and was the first retina to sport a selenium light meter (read “powered by the sun, and totally awesome”). Breaking from the previous models, the lens was now supported by a track built into the body itself, rather than relying on support from the more fragile lens cover door. When extending the lens, I can honestly say it feels solid…almost as much as a non-folding SLR. This folding and unfolding action is fast, accurate, and easy to do without much practice. Additionally, bellows were now completely contained within the camera body rather than exposed, giving the camera a more robust feel, and making light-leaks much less likely (this especially helps when purchasing a camera this old, as often exposed bellows are cracked and contain holes).

Even unfolded, the camera isn’t that large. Just the right size in my opinion. It fits into a camera bag easily, and isn’t much bigger than a lens-less slr body.

When the shutter fires, don’t worry about waking up the town (like I do when shooting my Bronica S2a). The leaf shutter fires incredibly silently, allowing covert street photography and a respectfulness in situations where noisy SLRs might be undesired. For those unfamiliar with leaf shutters, they are built into the lens itself, rather than the back of the camera near the film. Aside from a few other benefits (notably, better flash-sync speeds), noise reduction is the largest benefit for many. I’ve often had people take a second image, thinking the first didn’t work. The camera’s meter is uncoupled, meaning it simply serves as a guide for exposure…all adjustments must then be made manually. Exposure on the camera is done with the EV scale. I will say, I didn’t have much exposure to the EV scale before using this camera, but found it to be very fast and easy to use. Why did we ever abandon this method?

For those unfamiliar, the Retina is the typical rangefinder design still utilized by Leica and others. In other words, looking through the viewfinder doesn’t show you directly what the lens is seeing. Instead, the viewfinder shows you an approximation. While many people prefer to see exactly what they’re capturing, a good rangefinder will get you close enough with frame lines and compensation based upon the lens. Additionally, the rangefinder design allows for smaller camera bodies as mirrors aren’t required to reflect the image into the prism. On the downside, you won’t be able to tell if your lens is partially covered by a stray finger, or a lens cap. Lucky for all of us, the integrated lens cap on the Retina removes the need for a separate cap…just be sure to watch your grip!

Focusing is done by matching up two superimposed images that show through the viewfinder. If you’re used to an slr, there might be a slight learning curve, but it shouldn’t take long to master. I will say that the viewfinder is likely the weakest point of this camera, in my opinion. Thankfully, it is just large enough to focus, although it’s a far cry from what many of us are used to with SLRs of almost any kind. Also, if you wear glasses, you may have some issues because you really have to slam your eye against it to see the full field of view. Honestly, though, this is really my only complaint. The later variation, III large C (you’ll notice a lot of eBay listings will advertise this), added a larger and brighter viewfinder which is much better, but often commands over $100 more. Winding is done by a lever on the bottom of the camera, which frees up some space on the top of the camera. For someone who most frequently uses a Nikon F3, the winding action took a bit of getting used to, but it isn’t ill-thought-out.

While every feature I spoke about above makes this camera simply fantastic, at the end of the day, film cameras are essentially light boxes. Without a good lens, you simply won’t produce clean images. Thankfully, the lens may be the IIIc’s most impressive selling point. Sporting a fantastic f/2 50mm Schneider-Kreuznach Xenon C, images from this camera are surprisingly sharp…like staggeringly sharp for a camera of this age. As I’ve stated in my previous posts, I like sharp lenses, and while I love the look of vintage glass (this site is called That Vintage Lens, after all), I love vintage glass that’s sharp even more. You can also use a couple other lenses on this camera if so desired, (of 80mm and 35mm variants), although you can’t close the camera with those lenses mounted.

Remember to hold the camera carefully. Covering the light meter or the lens by accident could cause problems. It can be a little awkward at first, but then you’ll get used to it.

Using the Camera

I will say, using this camera has been a tremendous treat. Although I wish the primary lens was of the 35mm variety, this camera gives me almost everything I’ve wanted in a manual 35mm camera. It still sports a meter (which I will say, is pretty accurate), doesn’t require batteries, folds compactly while covering the lens in the process, and oozes quality. There are certainly times when I enjoy shooting with something that has full auto, like a Canon 1V or a Nikon 28ti, but often I just want to get back to the basics. Give me something manual that feels good in the hand and looks good on my side.

On that note, I love the look of this camera. Those who know me know that appearance is nearly as high on my list as usability and quality. If I can’t have all three, I usually don’t buy it. I’ve even passed up on purchasing quality hard drives for my workstation because they looked ugly on a desk. Give me beauty and brains when it comes to my purchases, or give me nothing at all. Thankfully, this camera has both.

I think a lot of people might wonder why I write so much about the historical standpoint of each camera about which I write. To a certain extent, it doesn’t really matter. History doesn’t determine whether the camera is a quality camera. And yet for some reason, the history of a camera determines quite a bit for me. I want to know why designed it, who built it…what cameras came before and what problems they were trying to solve. All of that adds to the intrigue, and the character. Part of why I love this camera is that it marked the end of an era for Kodak. Never again would they produce a camera of such quality, with such exacting detail. That makes it unique in my eyes. It gives the camera a sort of secondary purpose: to remind us of what was and how things used to be. Perhaps this reminder will inspire us to change what will be.

Some people might laugh at me, but film photography is appealing to me for a great many reasons, including the way it makes me feel. Shooting a nearly 70 year old camera makes me feel like I’m stepping back in time…like I’m re-living days of a bygone era. It takes me away from a world obsessed with electronics and auto-everything and makes me think…makes me feel. No doubt this is one of the reasons I love this camera. It just feels different than anything else I use, whether rangefinder or SLR. It has enough familiarity to be easily usable, but enough difference to feel unique, and dare I say, exotic. It gets looks, questions, comments. It feels like operating a high-end Swiss watch. It captures beautiful imagery. I shoot a lot of cameras, and this stands as one of my favorites as I’m sure you can tell, it has a lot going for it.

If you like this review and want to see more, feel free to share the article and subscribe. Perhaps this can inform another photographer as well! I don’t make any money from this site, I just want to see the information in the hands of as many people as possible. Also, feel free to comment below and let me know if you have any questions, comments about the article, or if you just want to know where you can get your own Retina IIIc!

*My Retina was purchased from and serviced by Central Camera of Chicago. If you’re ever in the area, be sure to check them out. They’re a phenomenal photo store with incredibly knowledgeable people, and a range of cameras you will be hard pressed to find elsewhere.

My retina came in a leather case. The outside can be removed to reveal a half-case that the camera screws into. Great for protecting your camera in style.

Here’s the back of the camera with the Retina logo. We also see the viewfinder window and the button used to reset the film counter. This is done manually when you finish a roll.

The camera uses the EV scale, which essentially connects the aperture and shutter speed on the camera. I find it very simple and easy to use. Just follow the reading from the light meter (listed on top) and adjust the EV settings. Then you’re all set to shoot!

Notice the EV selector under the lens. This is indicated by the numbers 2-18. We also see the knob that is used to help turn the lens for focus. The camera can only be folded when focus is set to infinity.

Here’s the top of the camera. We see the film knob, cold shoe, film counter (it is reset manually with the button next to it as well as the button on back), the shutter release, and the light meter with EV scale.

Here’s the camera opened up. It takes regular old 35mm cartridges and loads like any ordinary film camera.

Closed, the camera is tiny. Not only will it easily fit in a coat pocket or jacket pocket, but there is no need for a lens cap, because the integrated one protects the camera perfectly. Opening is simple. Just pull the button on the front, and swing open the cover door. This pulls the lens into place.

I love chrome on cameras. Just makes them shine!

Here’s the camera bottom. From left to right, we have the film advance lever, a connector for a special flash unit for the camera, and the twisting lock for the film door, which surrounds the 1/4” mounting point.

Here’s how it looks in my hands. Absolutely one of my favorite cameras. So classic, so well made, and such a fabulous picture-taker.